Photographer Andres Paomees, who comes from a marketing background, collects stories of free-flowing moments, fleeting light and memorable characters. His vertical frames and 40mm world form a recognisable, retro-tinged aesthetic shaped by a well-trained eye and the habit of roaming with one trusted camera and lens.

We spoke with Andres about how this direct and honest approach evolved, what street photography means to him, and why he believes authenticity is slowly fading today.

How and when did you discover street photography?

Back in school I actually started with nature photography. At the time it didn’t occur to me that street photography might one day matter to me. Later I began documenting my own life, and my interest in street photography really appeared during COVID times.

I needed some mental rest, to take walks, and I grabbed the camera. At first I photographed only for myself, I didn’t share photos with anyone. This came a couple of years later.

What is street photography to you?

It’s almost as broad a question as asking about the meaning of life. I recently had a long discussion about this with someone. It’s a pity that the field is so fragmented.

For example, I don’t post everything to the local street photography Facebook group because I feel they expect something different from what I do. For me, a street photo should include a person or at least some trace of human presence, like a steaming cigarette next to a cup of coffee. Pure architecture is something else.

I think street photography falls into two categories:

- those, who approach it as documentary work, where the content matters more than how the image looks;

- and those (where I see myself) who search for beauty, composition and light, but still strictly on the street, not in a studio. You look for that person or detail that completes the frame.

What draws you to street photography?

It allows me to express inspiration and creativity without big prep or cost. You just take the camera and go out – search for the light, play with composition, no need to chase models or book studios.

Sometimes I’ll go to outdoor events in town, not to photograph the event itself, but to use the opportunity – lots of people in one place – hoping to spot something interesting.

In Rome, near the Trevi Fountain, a magazine even featured my images because instead of shooting the fountain, I photographed the people taking selfies. I liked the perspective, and it stood out to others too.

Often I walk, looking for light and a frame, and wait for the right subject to enter it. I joke that I’m usually waiting for the woman in a red dress and a hat… She usually doesn’t show up though.

How long do you usually wait?

I don’t stay in one place all day. Fifteen minutes, max. If nothing happens, it wasn’t meant to be.

Usually I frame the spot first and imagine who would fit perfectly. If someone similar appears, I shoot. And if the woman in the red dress is close by, I run after her. My partner already recognises that look in my eyes and knows she needs to hold my stuff while I chase someone down.

Do you have role models?

At first I followed other photographers more, now less. At one point I realised my own style was drifting toward that of one specific photographer. It was subconscious. In one hand it helps your style develop, but it also limits you.

These days I look for photographers whose work creates a feeling, not those whose style I want to imitate.

I just came from a bookstore where I bought John Dolan’s wedding photography book The Perfect Imperfect. I’ve shot two weddings and swore I’d never do it again, but the book resonated with me, because of its imperfection. It boosted my confidence: not everything needs to be perfect. Beauty can live in imperfection.

It´s a good message in a time when social media pushes for the opposite.

Exactly. I’ve even been criticised for having too-straight lines, or for not shooting everything with a 28 mm, or for having everything in focus. It made me think, why should I?

Until this year I didn’t edit my photos at all. No masking, no manipulation. Many photographers mask their shots, paint with the light. For me, that’s no longer photography. If I see beautiful light on the street, I use it: I set up the frame, sit, wait for someone, and make the image in-camera. I don’t fuss over it afterward. That’s an art in itself.

I also shoot only JPEG, never RAW.

How much do you shoot on the street?

With friends we’ve discussed how your home town becomes visually monotonous over time, and you lose motivation.

Abroad it always feels like there’s more light, more interesting shadows, different people. Then I wonder: am I a street photographer or a travel photographer?

Do you have favourite spots?

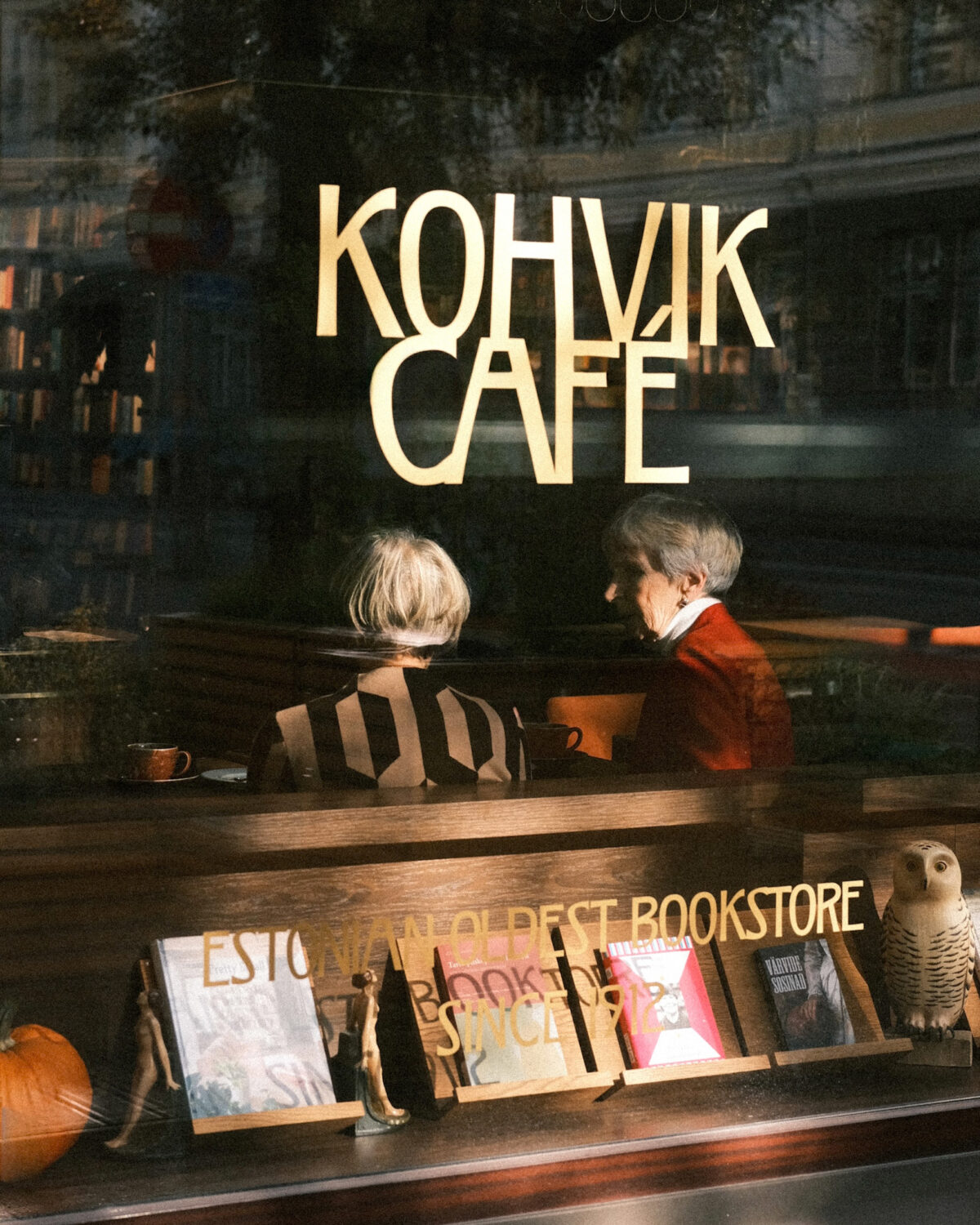

For the past two years I haven’t lived in Tallinn, so taking photos has become harder. Before, I would walk around for a couple of hours, sit in a café, and repeat that several times a week. Saturday mornings, while my son was at choir practice, I went for it as well. I miss that routine.

My go-to areas were the Old Town, the Balti Jaam Station and Telliskivi – places where you can also sit and rest. I don’t rush for two hours straight: I slow my pace.

In Mustamäe or Lasnamäe that’s harder. No matter how discreet you try to be, walking with a camera there makes everyone stare like you’re contagious. You get scared to press the shutter. But generally, I’m not shy.

Is shooting abroad easier?

Not really. My marketing background probably influences how I shoot. I think in series rather than single moments. Usually you need 5–10 frames to tell one story.

Whether I’m in Tirana or Tallinn, I think the same way: you need a wide angle shot, then people, then details. I’m only satisfied once I’ve collected all of it.

On Instagram I hardly ever post single images, almost everything is a series.

Your images are stylistically consistent and very authentic. How did you find your style?

Thank you – that’s a big compliment. Someone recently told me they followed me because of my clear visual signature.

I used to shoot Fujifilm and thought the magic was in the colours because I always use the same settings. Now I shoot film and digital side by side, and something stays the same anyway.

I think it’s my framing because I’ve intentionally limited myself: I shoot only vertically and almost always with a 40 mm lens (27 mm on crop).

These limitations have helped me grow tremendously. Even without the camera, I notice potential frames instantly. And if the space is too tight or too wide, or vertical shooting isn’t possible, I skip it and walk on. It simply wasn’t my frame.

a selection of photos by Andres

Do you carry this approach into your work?

Yes. On commercial shoots I first deliver the required shots, then see if I can create something for myself, like details, a wide shot, a small series…

This year I shot the PÖFF (Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival – AH) campaign and portraits. The client was happy, but I felt something was missing in the series, so I shot a few extra images. All on film, so I couldn’t check the results. Just as we were leaving, I realised there was one frame missing. So I asked the model to put her shoes back on and shot an out-of-focus frame where she is leaving. I felt it wrapped the whole session together.

Most of my clients come through Instagram. Agencies usually say, thats Estonia is full of photographers, but very few have the backbone to stick to their style. But those are the ones agencies look for.

One client even found me through the photos of Keskturg (Central Market) session while I was shooting street photos. They’ve now been with me for a year.

This market can be a tough place for street photographers though.

It has inspiring environment but it´s difficult yes. I have official permission, but it doesn’t matter – the vendors there have been around for 40 years, and they don’t care who you are

You need good storytelling skills. In the meat section you chat, make a deal and if you want a photo, you buy half a kilo of mince. If one vendor refuses, another might help by talking them into it.

One woman, selling sauerkraut didn’t want to be photographed. I promised to print the photo and bring it to her, then she agreed. A bit of diplomacy goes a long way.

You also shoot portraits on the street. How do you approach people?

Since switching to Leica, manual focus makes shooting a bit harder, because you need time to focus through the viewfinder.

So I look for permission or agreement in their eyes. Often no words are needed.

Recently in Greece a man was standing on a balcony hanging laundry. I waved, he waved back. I lifted the camera, took the shot, thanked him, and walked away. That’s it.

It pushes you out of your comfort zone. I don’t love asking strangers for a photo, but sometimes you have to.

What should beginners keep in mind when photographing while traveling?

Do some research: what’s allowed and what isn’t. I recently did a study in university for an assignment on the ethics of street photography. In Estonia, ethics is the main regulator – our media room is quite free.

Elsewhere laws or customs differ. When traveling, I usually act like a clueless tourist. I carry my camera around my neck and look like a Japanese tourist. You walk around, snap quick and nobody minds.

Why did you switch to analogue?

The camera has to be something you want to take with you. DSLRs felt like something I carried out of obligation. A camera is an accessory for me, I carry it daily because you never know when a moment appears.

I once used the Fuji GFX, which is fantastic, but too big for the street – it scares people. Small cameras are more discreet. That led me to Leica. Since I was already used to not editing my photos, I tried 35 mm film. The tones right out of the camera were perfect.

Now I shoot both digital and film. Each has its pros and cons. What matters is that the camera is small and discreet.

How do you find the motivation to take photos when inspiration is lacking?

That’s the hardest part. When you’re mentally low, no good photo comes out. Sometimes you just need to rest. Once in summer I didn’t touch the camera for a month, and when I picked it up again, the excitement returned.

I don’t shoot with my phone except for water meter readings, that motivates me to always bring the camera so moments don’t slip by.

Let´s imagine: if you would have to make a book of your street photos, what would be the theme?

I’ve thought about this. Last year Fujifilm magazine did a feature on me and asked for 50 of my best images. When I saw the magazine, I realised there is a common topic running through my work.

Maybe the topic would be how much you can achieve without editing, and how much a trained eye can create images in-camera. That was my original idea, though who knows – life will decide whether a book or exhibition eventually happens.

Do you have any tips for beginners?

Choose one camera and one fixed lens. Decide whether you shoot vertical or horizontal. It helps you focus and train your eye.

Limitations that feel restrictive at first are not actually restrictions, but they make you think creatively.

For example, when traveling in Europe’s narrow streets with a 40–50 mm lens, you might wonder what to do. You want the street and the vendor in the frame. Then you have to figure it out – that’s how you grow.

And invest in plane tickets, not lenses. Practice matters more.

Finish the sentence: “I photograph because…”

“…I don’t know how not to.” Laughs.

It has become such a big part of my life that I can’t imagine being without it. I’m glad it has stayed with me, because many professional photographers started the same way, but now they use their cameras only for work. I don’t want that.

The worst thing that could happen on a trip is arriving at the airport and realising you left the camera at home. I’d probably buy a new one on the spot. I’d survive more easily without a wallet or a phone.

Can you share a story behind one of your photos?

Yes, it was Thursday, October 6th, a beautiful autumn day. As every Thursday, I had taken my son to choir practice in Tallinn’s Old Town.

Choir lasts exactly one hour. I had promised myself that during this hour I would wander the Old Town with my camera. I had walked nearly whole hour without taking a single photo. I felt it just wasn’t my day.

On my way to pick up my son, nearing the Sõprus Kino cinema, I noticed an interesting play of colours between the columns. I tried to capture it but couldn’t make it work. I accepted that the day wasn’t meant for photos.

I walked past the cinema, turned back once more and thought: fine, at least take one shot of the columns, so I don’t go home without pressing the shutter at all.

Exactly at that moment, a girl in a coat and holding a bouquet appeared between the columns, peeking out. I pressed the shutter.

She disappeared as quickly as she appeared, and I hurried off, I was late. Walking away, I immediately knew I had caught the moment. Later at home, thinking about it, I realised the clock had just struck the hour. The girl in the frame had been waiting for someone who had only a few minutes left to make it to their screening.

Two people in a hurry crossed paths that day and one of them happened to have a camera.

You can find more photos of Andres Paomees on his Instagram page.